Author Dominic Stevenson on Football’s Troubled Relationship with Mental Health

Changing the discussion around mental health in the beautiful game- Dominic Stevenson (pictured)

Mental health in football has undoubtedly been neglected for far too long.

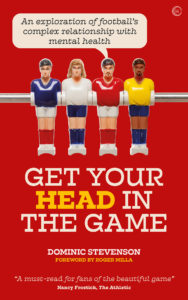

Dominic Stevenson is seeking to change that. In his new book, Get Your Head in the Game, Stevenson takes on the challenge of shedding light on a side of the beautiful game that, for too long, had been pushed into the shadows.

A devout Sheffield Wednesday fan, despite growing up in Grimsby, North East Lincolnshire, Stevenson is no stranger to the world of football. Stevenson began his journey at youth level, where, despite injuries such as a broken arm and concussion (which left him suffering from migraines), he was able to continue up the ladder.

Indeed, Stevenson eventually captained his team, West Lindsey Juniors, on a memorable tour of Nepal, where much to their surprise, they were believed to be the England national team.

It is through coaching though, at League Two academies in England and Scotland, that Stevenson has been able to develop his understanding of the game, and the struggles it has around mental health.

However, the inspiration for the book came not from his experiences in the dressing room, but as a fan witnessing the abuse of a 20-year-old Wednesday goalkeeper by the supporters around him.

“Cameron Dawson was making one of his first appearances for the club. There was a penalty kick and he saved it, everyone was cheering him on and he was going down in history. Then two minutes later he miskicked it and it went out for a throw in and he was getting dogs [verbal] abuse, and I just thought: ‘He’s 20. Does he deserve this?’ I just thought: ‘How do people cope?’”

Tragically, in recent weeks the mental health of the nation’s footballers has been in the spotlight, specifically those at the youth academy level.

Jeremy Wisten was only 18 years old when he was found to have taken his own life on the October 24th 2020. The death of the former Manchester City youth player is the latest in a growing list of academy footballers who believed they had no other choice.

“It’s happened before, and it’ll happen again,” said Stevenson. In his opinion, the public and the media are too quick to point the finger of blame at the academies themselves.

“People view it as ‘that young man had mental health problems so he’s weak, and Man City should have toughened him up and made him feel better’. But if he had cancer and died, nobody would say ‘the radiologists at Manchester City weren’t very good.’”

Spotlighting the stories needing to be told. Get Your Head in the Game is out December 8th

The Role of Social Media

It is clear though that there is a huge disparity of facilities at the academies at the top, and those lower down. Social media awareness and training is one aspect where this is abundantly clear, as Stevenson found in his research.

“At Man United, under Nick Cox, I know they are very well-trained, and they have sessions with the first team players talking to them about the use of social media, talking about how to interact with people. They even have Marcus Rashford coming in and talking to them about dealing with the media.

“Then you go down to Stevenage and all of a sudden, you’ve got one pitch on a public play area, you’ve got minimal staff. You’ve got £10 an hour part time coaches leading it. It’s such a huge disparity.”

Yet, despite many coming into the game now being what Stevenson calls – “social media natives” – he believes that many players are now, for their own mental wellbeing, turning their backs on social media.

“There seems to be a lot of footballers now who are drifting away from social media. Their accounts are becoming private, and very few are responding to Instagram stories. Players might now only tweet if they sign for a new club or if they do a charity appeal, and then when they leave, they’ll do a tweet.

“If you expose yourself on social media, people become more aware of who you are and there can be repercussions for that.”

The Need to Talk

But, even if players can shut out the torrent of abuse many get on social media, there will still be those who will find themselves confronting spells of mental illness. Then, for Stevenson, the problem becomes their inability to be open with their struggles.

“I want footballers to feel more confident and more able to come out with these issues, because we hear about them because they have reached a point of crises, and I don’t want to hear about it when they’ve reached a point of crises, I want to hear about it six months earlier.

“I want my favourite player to take a month off playing so they can get their head right. What I don’t want is to get to the end of the season, having spent nine months being under the cosh, and feeling like they’ve got no choice but to do something like take their own life.”

On the impact of Covid-19, Stevenson also emphasises importance of supporting fans who, without live football, may be struggling.

“Everything points to the fact that once Covid is over, we are going to have a mental health crisis in this country for years to come. Until our generation is dead, we will feel the effects of this year because it has destroyed people and we don’t have the mental health infrastructure to deal with it.”

Get Your Head in the Game is one of those works that the importance of which cannot be understated, especially in this current climate. Going forward, one can only hope its message of mental health awareness and understanding in the football community does not go unheard.

Get Your Head in the Game is published by Watkins Media and is out in paperback on the 8th of December 2020 for £12.99.

If you or someone you know is struggling, UK mental health charity Mind maintain a list of helplines and services.

And if you’re reading this from outside the UK, you can find a service near you at CheckPoint.Org.