It’s Business, Not Personal: Broken dreams in academy football

Just like any other industry, football is a business. The success of a business relies on results.

Since football has become increasingly commercialised, there are a number of facets to youth development which pose very clear and very troubling problems.

Firstly, the competition is fierce. I mean really fierce.

Michael Calvin, author of ‘No Hunger in Paradise’ – a book which provides an insight into the difficulties of competitive youth football, estimates that only 180 of the 1.5 million players who are playing organised youth football in the UK at any one time will make it as a Premier League professional.

That equates to a success rate of 0.012%.

“It’s not a business you can go into if you want to do it, you have to need to do it” said Michael.

The chances of accomplishing this feat are astronomically thin and those working on the academy production-line knows this. The question is whether this message is being clearly communicated.

Young players are told that it’s an extremely hard profession to break into, but what does that really mean to an 11-year-old?

Even if their parent or guardian fully understands the challenges and sacrifices their child will have to undergo in order to make it as a professional footballer, the truth is, expectation and excitement sky-rockets when a player is taken on at academy level.

In this sort of environment, where coaches are constantly reminding you how lucky you are to be there, whilst highlighting how much work you still have to do creates a bi-product. That is, the development of a strong athletic identity at an extremely early age.

When individuals make premature commitments to occupational or ideological identities such as the extreme professionalism required to succeed as a footballer, they can end up missing out on wider developmental experiences that would better prepare them for life after football. This is called athletic identity foreclosure.

The commitment to this role may provide a sense of emotional safety, but is done at the expense of psychological growth and personal freedoms, both of which should be of paramount importance for a child or young adult.

The sad reality is that this commitment to that athletic identity is exactly what coaches are looking for when they sign players up.

Michael said: “You’re looking for that edge, that willingness to be the best that not all kids have. But those kids are immature both mentally and physically, they need guidance in a holistic sense which football doesn’t give you as well as it should.

“They have welfare officers and things like that but it’s a hugely imperfect system.” He said.

Despite the development system asking young players to commit 100%, the manner in which players are released is often insensitive.

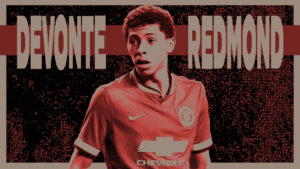

Former Manchester United academy prospect Devonte Redmond revealed that he first learned he was being released by the club on Twitter after five years with the club.

Speaking to The Athletic, Redmond said: “I looked at my phone. All of a sudden, I’d got loads of notifications on Twitter. ‘All the best’ – lots of messages like that. It was really strange.”

Regardless of a players’ ability, this is the wrong way to manage anyone’s dismissal. Proper care should be taken to manage a young players emotions and welfare after their release.

Too many have their dreams crushed when they could simply have been reassessed.

The reactive nature of football as an industry means that there now exist a number of clubs and external organisations which claim to focus on managing the welfare of released players.

But Michael believes we should keep our optimism on hold saying: “I’m sure people will say that improvements have been made on player welfare and look at the packages we offer now“.

“That’s great on paper, but football isn’t played on a piece of paper. It’s governed by so many emotions, so many different instincts and most importantly… so many vested interests.”

There is no denying the current state of play. The development football system has become increasingly toxic as the ills of the senior game have trickled down.

Greed and opportunism have created a cut-throat environment where elite players who are essentially only children are forced to push themselves to extreme mental and physical limits, often at the cost of psychological balance.

Whilst Michael is sceptical of football’s current state with regard to academy players’ welfare, he hopes that development football in England is slowly transforming into a more empathetic and player focused industry.