Cardiac arrest among black footballers

Cardiac arrest occurs when the heart suddenly and unexpectedly stops pumping blood around the body. It is a life-threatening event that affects one in 17,000 young athletes per year.

Although a rare occurrence, sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) remains the most common medical cause of death among footballers, and studies over the years have shown that black players are at increased risk.

What causes SCA among footballers?

Professor Michael Papadakis is a Professor of Cardiology at St George’s, University of London, and emphasises genetic factors as the primary cause of SCA amongst younger athletes.

“Once you go past your mid-30s, the most likely cause of SCA is coronary artery disease, which causes heart attacks and strokes.

“However, with younger athletes we look for inherited diseases passed on through our DNA, or congenital conditions that someone was born with,” he says.

Nwankwo Kanu was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect after his Inter Milan medical in 1996. Successful surgery saw his aortic valve replaced, and he went on to have a hugely successful career.

Dr Ravi Assomull, Consultant Cardiologist at One Heart Clinic reiterates this. He says, “People often dismiss someone collapsing and dying as a heart attack.

“In your 40s and 50s it’s likely to be a heart attack. But in young people it’s likely to be a genetic condition, resulting in a ventricular arrhythmia (VA) and sudden cardiac death (SCD).”

Raphael Dwamena tragically died on 11th November 2023 after suffering cardiac arrest while playing for Egnatia Rrogozhine. A failed medical to Brighton & Hove Albion in 2017 revealed he had a ventricular arrhythmia.

FIFA Sudden Death Register (FIFA-SDR)

Between 2014 and 2018, FIFA investigated worldwide sudden death in football through its Sudden Death Register. To meet the criteria, a player would have to suffer SCA during football-specific activity, or up to one hour after participating in training or a game.

Of the 617 cases over the period, a specific cause of death was documented in 211 of them, with SCA accounting for 51.

Cardiomyopathies, which are diseases of the heart muscle affecting its size, shape, or thickness, were the second biggest cause of SCD amongst players 35 and below (18 percent), as 22 percent of cases were left “unexplained” due to autopsies revealing no signs of cardiac disease.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) was the most frequently reported cardiomyopathy among the players, and in FIFA’s SDR, black players had the highest percentage of cardiomyopathies (28) and the second-highest percentage of HCM (nine) among all ethnic groups.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM)

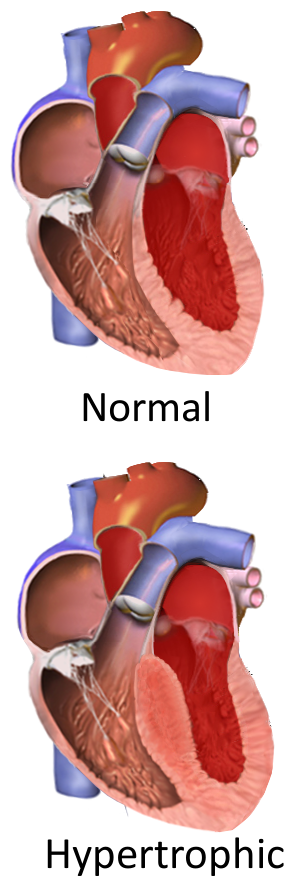

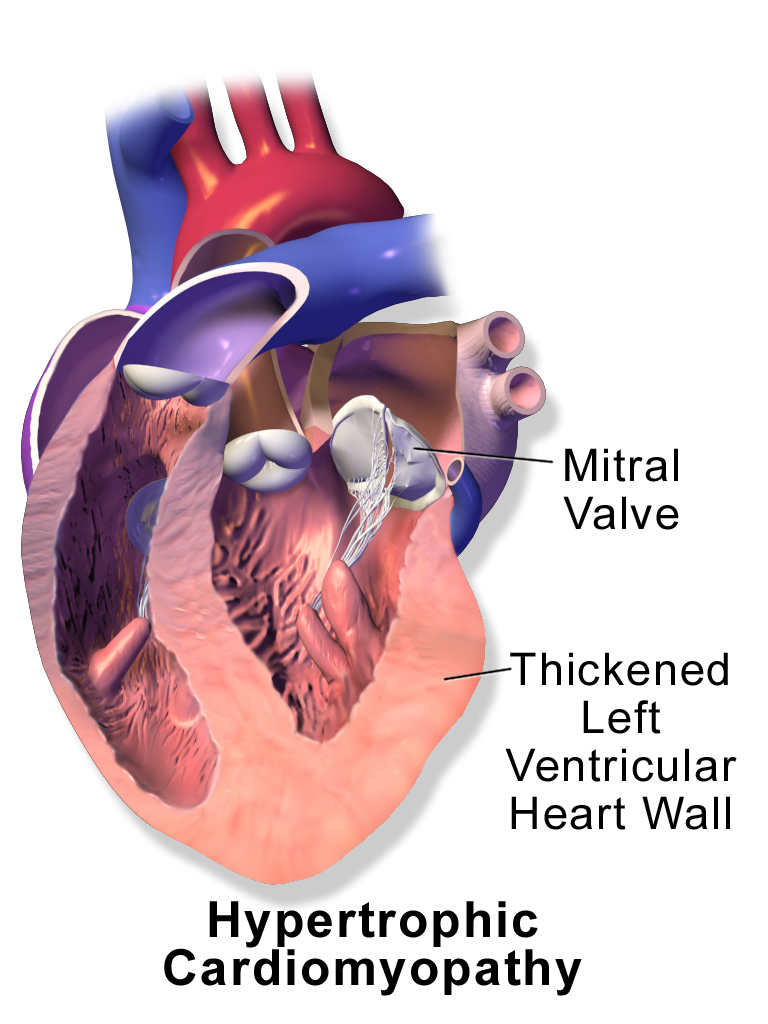

HCM is a genetic condition in which the muscle wall of the left ventricle, the heart’s main pumping chamber, becomes thickened (hypertrophied) and stiff.

This thickening means the heart can not take in, or pump out enough blood during each heartbeat to the rest of the body.

Npatchett at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

HCM, like many cardiac diseases among footballers can go undiagnosed, because as Professor Papadakis explains, “If we look at athletes who had cardiac arrest, we know that up to 80 percent of them never had any symptoms, or any significant family history [suggestive of a heart condition] to warn us.”

Samuel Eto’o and Rigobert Song hold up a picture of Marc-Vivien Foé, who tragically died after collapsing on the pitch during the 2003 FIFA Confederations Cup semi-final. His autopsy revealed he had Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy.

Black players at increased risk

The majority of footballers’ hearts go through physiological (normal) electrical, functional, and structural cardiac adaptations when they exercise at high levels, which is commonly known as Athlete’s heart.

One of these structural cardiac adaptations that occur is Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (LVH), which is the thickening of the walls of the left ventricle, a similar occurrence to the aforementioned genetic condition of HCM.

Blausen Medical Communications, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

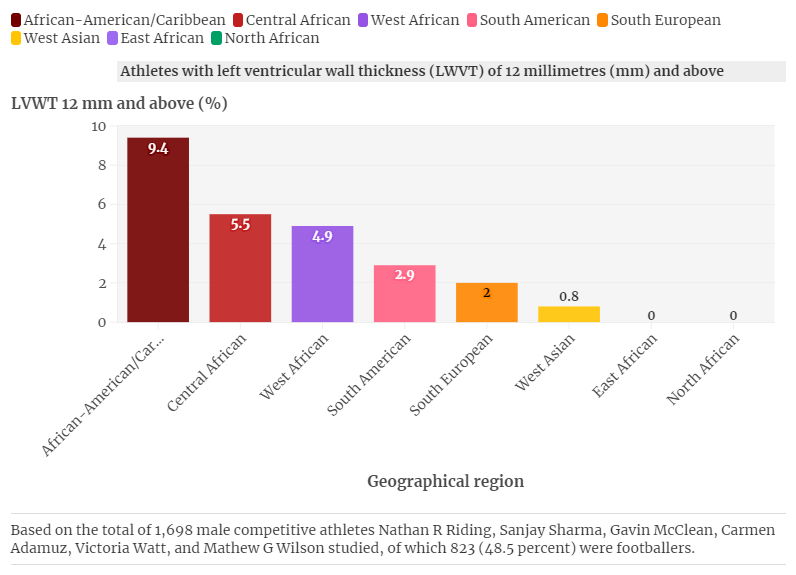

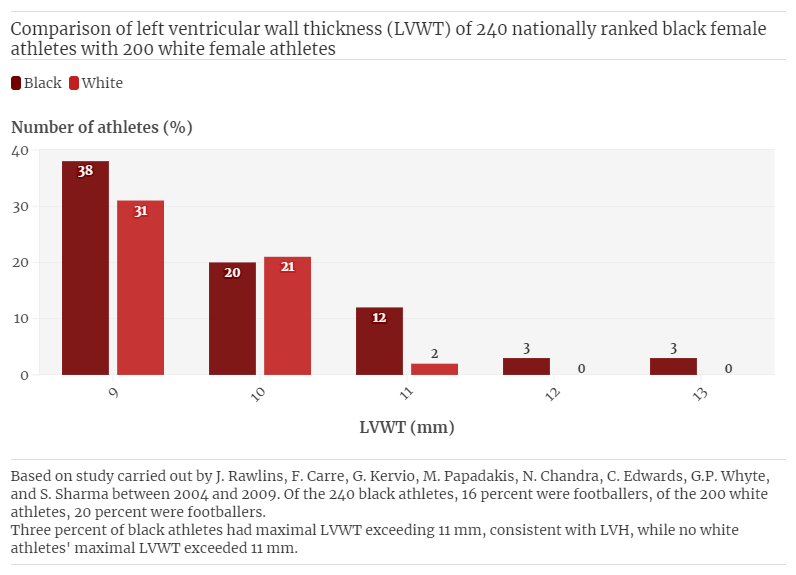

Black footballers exhibit a disproportionately higher frequency of LVH compared to players from other ethnic groups, meaning their left ventricular heart walls naturally thicken more during intense exercise.

Therefore, when examining their hearts it is difficult to differentiate between physiological (normal) LVH consistent with Athlete’s heart, and pathological (abnormal) LVH consistent with the genetic condition of HCM.

As HCM, the most commonly detected cardiac disease among footballers suffering SCA, also affects the left ventricle.

Professor Papadakis says, “One percent of white athletes may have a thicker ventricle, that percentage can be 12-15 among black athletes.”

Males

Uchenna Ozo and Sanjay Sharma’s 2020 paper for the European Cardiology Review, which looked at the impact of ethnicity on cardiac adaptation, stated:

Uchenna Ozo and Sanjay Sharma’s 2020 paper for the European Cardiology Review, which looked at the impact of ethnicity on cardiac adaptation, stated:

“LV hypertrophy is more prevalent in black male, female and adolescent athletes than their white counterparts.”

Females

Difficulty in differentiating between physiology and pathology in black players

Difficulty in differentiating between physiology and pathology in black players

Professor Papadakis explains that:

“As black athletes have a higher prevalence of LVH, it can be far more challenging to differentiate what is normal and what is abnormal, because the overlap, or what we call the grey zone between physiology and pathology, and the signs that can cause confusion when you’re assessing an athlete, are much greater in the black athlete compared to the white athlete.”

Professor Papdakis continues, “That’s why expertise, particularly when you are assessing a black athlete is very important, because if you say to someone that this [LVH] is because of exercise, but they’ve actually got an underlying heart disease that you’ve missed, you may be putting their life at risk.

“Or conversely, if you label someone with heart disease, while all you are seeing is the effect of exercise on their heart, you may falsely label them with a condition, and that will have implications in terms of how much sport they play and whether they can continue with their competitive careers.”

Former Brighton midfielder Enock Mwepu was forced to retire in October 2022 after being diagnosed with a hereditary cardiac condition, which was not previously evident despite regular screening.

In Dr Assomull’s experience, “There have been players that I have screened who have subsequently gone on and played, and every time you see them you worry that they could collapse.

“Even in the most skilled hands and with the most eminent cardiologists, people have been screened as fit and drop dead, and they tend to be Afro-Caribbean, it’s really difficult.”

Pallbearers carrying the coffin of Cheick Tioté, who tragically died after suffering cardiac arrest during a training session for Chinese League One side Beijing Enterprises Group, on 5th June 2017.

Why do black players’ hearts thicken more during intense exercise?

As Professor Papadakis highlights, “We assume there is a genetic element to it, meaning there is something different in their DNA that makes them more predisposed to thickened ventricles when they exercise.

“For most individuals, we assume it is physiological and beneficial, and something good that exercise creates. But in some of them [black players] this will not be the case.

“With the heart muscle, it’s not always necessarily the case that the thicker it is, the better it is.”

Samuel Okwaraji’s case evidences this. On 12th August 1989, he collapsed on the pitch during a 1990 FIFA World Cup qualifier while playing for Nigeria against Angola.

Okwaraji died due to complications from HCM. However, his autopsy also revealed that the 25-year-old had an enlarged heart.

Last picture of Samuel Okwaraji alive. Referee Hounnake Kouassi gave Samuel Okwaraji his last yellow card in the 71st minute of the 1989 World Cup qualifying match between Nigeria and Angola at the National Stadium Surulere, Lagos, August 12, 1989. And he died in the 77th minute. pic.twitter.com/5m93BLFe20

— Nigeria Stories (@NigeriaStories) January 29, 2024

Important steps going forward

Dr Assomull says, “As a healthcare philosophy in the Western world we tend to be reactive. We wait for things to happen before we do something about it. We need to be proactive.

“There is no reason why every person should not see their GP during their adolescence, have their family history taken, have their heart listened to, and have an ECG taken.

“It is all doable but it needs a complete change in philosophy and mindset because that basic screening is not going on.

“There is definitive room for improvement, and if we do the basics properly the number of tragic incidents will be far less.”

Patrick Ekeng tragically died on 6th May 2016, after collapsing on the pitch while playing for Dinamo București. Elena Duta, the doctor in the ambulance which took Ekeng to the hospital, was later charged with medical negligence in his death.

To prevent as many incidents of cardiac arrest as possible, Professor Papadakis says we must, “Screen individuals with no symptoms and family history to see if they have an underlying cardiac condition.

“Evaluate and refer individuals with symptoms and family history suggestive of a heart condition to a specialist centre.

“Have emergency response plans in place during games, as well as training grounds to intervene if an athlete was to experience cardiac arrest.”

A good example of this is Fabrice Muamba. To save lives in the future, we must take action now.

Fabrice Muamba’s heart stopped for 78 minutes after suffering cardiac arrest in the FA Cup quarter-final on 17th March 2012. He was given 28 defibrillator shocks and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), which saved his life.

Feature image credit: Alpha Stock Images – http://alphastockimages.com/ Nick Youngson – link to – http://www.nyphotographic.com/