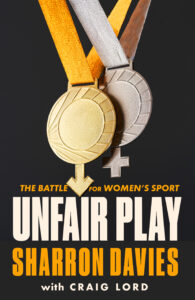

SG Reviews: Unfair Play: The Battle for Women’s Sport by Sharron Davies

Unfair Play: The Battle for Women’s Sport by Sharron Davies stands out like a sore thumb among the nominees for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year shortlist.

Writing alongside Olympics and swimming journalist, Craig Lord, Davies sets the scene of the state-led doping prevalent in Cold War-era East Germany that led to many athletes being awarded medals they should not have rightfully won.

Yet Unfair Play takes the turn towards conflating these instances of state-sponsored cheating, with the current issue of transgender inclusion in sport. A comparison that simply should not be made.

Ultimately, the book argues that trans women should not be allowed to compete in female categories in elite sport to protect the ‘fairness’ of women’s sport.

Taking a slightly different approach to the other reviews, this article will run through seven core premises of the book and provide a response.

1. Use of language and approach to trans people

The book frequently deadnames trans athletes when using them as examples. To ‘deadname’ is to use the former name of a trans person and shows a disregard for how they now identify which can invalidate their gender identity and who they are.

While Davies advocates for respect for all, by failing to respect the identity of trans athletes the book falls at the first hurdle. Regardless of any arguments the book makes, to deadname with such intent as is required in a thoroughly edited book does not set a tone of respect for trans people.

2. Conflating trans-inclusion with systemic doping

Davies foregrounds the book with her own personal account of losing out on gold to Petra Schneider, who later confessed to drug offences that would have enhanced her performance.

Experiences like these still clearly haunt Davies and are certainly an injustice to all those who missed out on medals as a result of East German state-doping. That, however, does not justify Davies’ perception of trans athletes.

She writes: “The science and biology that underpinned East Germany’s fraud has several parallels with the transgender debate.”

In doing so, Davies mischaracterises and misunderstands what it is to be transgender. Such a line of argument insinuates that trans women only transition in order to do better in sporting events, something which is fundamentally untrue.

State doping was a systemic practice of intentional deception to gain medals and international prestige for an entire nation and political ideology. To suggest parallels with trans athletes indicates a belief that this equates to deception.

It should not need saying but trans athletes do not go through transition in order to win medals but in order to align with their identity and gender orientation. To compete in a category that reflects the way you feel can be validating.

Unfair Play goes further and suggests that swimmer, Lia Thomas, carries “more guilt than the abused ranks of East Germans”.

Thomas commented to the BBC: “I also don’t need anybody’s permission to be myself and do the sport that I love.”

Hence by competing in the female category Thomas was merely exercising her right to be herself, rather than any act of wilful deceit alluded to by Unfair Play.

3. The extent of the perceived ‘problem’

The premise of Unfair Play claims that to include trans women in women’s sport is to threaten women’s sport itself.

Davies argues that once trans women are allowed to compete, cis women will be put off from competing and competition will cease to exist.

Such claims hugely exaggerate the extent of success that trans women have had in women’s sport. The very fact that in each sport Davies uses as an example, she is only able to find one or two examples of a trans woman who competes for titles in the sport illustrates the extent of the exaggeration.

More to the point, when looking for a trans woman who has competed to a level at which they have won major titles, the list becomes even less.

Hence, the “threat” to women’s sport that the book is premised on becomes much less justified when quantified with the number of trans women actually able to compete.

Laurel Hubbard, an example used by Davies and perhaps one of the most successful trans-athletes, still came last when competing in weightlifting in the Olympics.

Despite being the first openly trans woman athlete to compete at an Olympic Games and a winner in two Commonwealth Championships, she failed to register a successful lift at the Tokyo Olympics.

4. Lack of nuance around inclusion

Unfair Play and Sharron Davies takes a definition of sex that is devoid of nuance, or the sensitivity required in conversations about sex.

She states: “Females have one pair of identical X chromosomes – XX – and males have one X and one Y chromosome – XY. In all cases human biology delivers a male or a female.”

In reality, sex can be far more complex, something which has been evidenced numerous times in the sporting arena.

Sex testing, and the arbitrary measures of what determines sex, have changed throughout history in the field of sport and in culmination suggest there cannot be a determination by one single variant.

While Davies indicates that sex is clear cut, it is anything but. Science itself has been informed by a political context and the binary between male and female is no different. From phenotypical tests to testosterone tests, sex testing has used a multitude of arbitrary measures throughout its history to determine sex, each with its own flaw.

Moreover, when referring to sensitive and nuanced examples of DSD (Disorders of Sex Developments) and non-binary athletes, Davies labels them as “gotchas”.

She argues that, through DSD athletes, “male advantage finds its way into female competition” despite her example of Caster Semenya having identified as female since birth.

5. Context

Chapter 11, “The Gender Industry”, seeks to set the context of the book within contemporary society. Davies paints women as the victims of such an industry, criticising the capitalist circus that puts pressures on women in advertising and sponsorship deals.

In isolation, these claims appear entirely just. Yet Unfair Play does not argue that women lose out as a result of embedded systems of patriarchy, but rather that they lose out to trans women.

Using the example of TikToker Dylan Mulvaney, Davies suggests that cis women are being replaced by trans women in marketing campaigns, such as for the Nike sports bra. Yet this fails to recognise the reality of the climate for trans-athletes and transgender people full stop.

Mulvaney herself has received a deluge of online abuse and hatred and has been forced to limit her media presence as a result. That is someone in a relatively privileged position within the trans community with a platform and many allies.

In a Stonewall study in 2017, it was found that 94% of trans young people in the UK have thought about taking their own life. 1 in 10 trans pupils face death threats while at school.

The UK Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, was cheered for stating the ignorant jibe that “a man is a man, and a woman is a woman” at the most recent Conservative Party Conference. Among a worsening climate for trans rights it is clear they do not benefit from privilege.

Davies claims to be in a righteous minority, valiantly fighting for the rights of women. What the book fails to understand is that transgender athletes are oppressed under the same system of patriarchy as women also experience oppression.

By picking this battle, she is failing to recognise where the root of oppression lies.

6. Use of evidence

Unfair Play cites a range of studies to demonstrate the trans women in sport retain an advantage from experiencing male puberty when they move to women’s sport.

To Davies’ credit the book is thoroughly researched in finding scientific, peer-reviewed studies to support her argumentation.

She cites: “18 peer-reviewed studies (by spring 2023) that show that male advantages remain truly significant in sport even after years of hormone-reduction therapy.”

While this may be true, performance does not come down to just testosterone, these women still require a high degree of skill and talent to make it in elite sport.

Moreover, this evidence is based on an understanding of sex which assumes a clear-cut binary. While western science has perpetuated this idea, the issue is far more complex than this.

Science itself is not objective, and the very system of patriarchy that oppresses women, also implemented and maintains notions of a sex binary.

The very fact that sex testing in sport has gone through so many iterations demonstrates even science cannot come to a straight-forward conclusion on what exactly informs the divide between female and male.

Unfair Play must acknowledge that science, and the science used by Davies in the book, does not provide the straightforward proof it claims to.

7. ‘Fairness’ in sport

The main argument within the book boils down to demanding ‘fairness’ for cis women in sport.

It deems the advantages of trans women too great to allow ‘fair’ competition and thus wants to see women’s sport ring-fenced for cis women only.

‘Fairness’ itself is an ambiguous term, ‘fairness’ in sport even more so. Competitive sport has always come down to who has an advantage, many of these biological: which swimmer has a greater arm span, which high jumper is taller, which runner has a bigger lung capacity?

Advantages come from all over society; it is inherently unfair. Should people who attended private schools be excluded from competition because they had access to far greater resources throughout puberty?

Why, then, is the argument choosing to exclude trans women, who remain in the minority in sport?

Fighting to protect the rights of cis women, is to violate the rights of trans women to compete in sport in a category that validates their identity. Why is one set of rights being prioritised over another when the impact on cis women is so small and, if anything, is part of sport?

In the claim that Unfair Play seeks to protect women we must ask, which women?

Score: 1/5

(Click here to read Sports Gazette’s review of Kick the Latch, click here for the review of Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson and click here for the review of Concussed: Sport’s Uncomfortable Truth by Sam Peters. All books also on the shortlist.)