Show racism the red card, not the white paper

Racism won’t be punished in a political climate that facilitates it. The tech giants have the means to help, and it’s time they did.

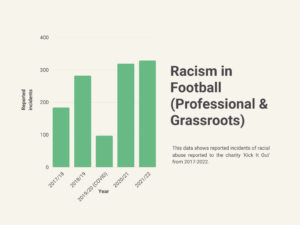

Data from Kick It Out shows that in England, there has been a year-on-year increase in reported incidents of racial abuse since their records began.

In 2021, after one game, last year’s figures were completely gulfed. England’s loss to Italy at Euro 2020 produced 600 reported incidents of online racial abuse. 11 people were arrested: a conviction rate of 1.8%.

The two most recent high-profile incidents came in two separate leagues. This is indeed a widespread problem, but has taken on a different, more prominent shape in Spain.

Real Madrid forward, Vinicius Junior, while assisting nine goals and scoring 19 of his own this season, has been the subject of racial abuse eight times this season. The most harrowing of which emerging after an effigy of the Brazilian star was hung over a bridge close to Real Madrid’s training centre.

The figures mentioned only reflect incidents that have led to official complaints from La Liga; how much racist abuse eludes the radar of football governing bodies is uncertain. But you could assert, with a degree of certainty, that the number is high. The data from Kick It Out would follow the same trend if unreported incidents were factored in.

Like Vinicius, Ivan Toney has recently been in the crosshairs of racists.

In February, the Brentford talisman was rewarded for a dominant display at the home of the league-leaders by a barrage of racial abuse over social media.

On Twitter, both Brentford and Arsenal condemned the abuse Toney received, and the majority of people rightly agreed that those behind the abuse aren’t fans of Arsenal. Nor are they fans of football, but rather a cancerous minority who stain the beautiful game with their vitriol.

https://twitter.com/BrentfordFC/status/1624749476874276864

But still, there were some in the replies offering their dense, uneducated two cents, suggesting that due to the controversial nature of Toney’s equaliser, the abuse he received was deserved.

When you see these comments – when fandom rears its ugly head – you begin to question if the problem of racism will ever be stamped out; whether it’s a systemic issue that spreads from generation to generation like a disease trying to survive. Whether initiatives like ‘Kick It Out’ or ‘No Room for Racism’ are fighting for a hopeless cause. The dream is noble, but the reality, bleak.

Football is sick, and the governing bodies that have the means to help find the vaccine either do what they can (which is little), or refuse to make the changes that could make a difference.

In Spain, La Liga say punishment for racism lies outside of their remit. The reports of racism they can file to legal bodies have never ended with prosecution.

UEFA and FIFA can seldom be labelled bastions of the oppressed, and moreover, think it’s okay and virtuous to rely on measly fines as recompense for racism.

The Premier League can condemn and castigate, but the problem will persist and evolve.

The Online Hate Safety Bill in England allows the government to fine social media companies that fail to expunge abuse from their sites. But is legislation even the answer?

Back in 2012, Scotland took the legislative route in an attempt to decelerate sectarianism at football matches. The Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act – which only applied to football fans – broadened the definition of ‘offensive behaviour’, but was heavily criticised by politicians and football fans alike.

The bill was seen as unnecessary because there was already legislation in place to stop disorder at football matches – as there is here in England. All the 2012 Act did was alienate football fans and accentuate tensions between supporters and the police on matchdays. The bill was eventually scrapped in 2018, with Scottish Labour Party politician, James Kelley declaring it, “the worst piece of legislation in the Scottish Parliament’s history”.

Should we be relying on the politicians whose policies have polarised and divided society, and contributed to the volatility of public discourse in the UK?

Home Secretary, Suella Braverman – when she’s not deporting asylum-seekers to Rwanda – refuses to apologise to Holocaust survivors for using language that dehumanises migrants. Adding this kind of rhetoric to the already-toxic climate only facilitates further hate. The riot in Liverpool last month is testament to that.

In 2019, then-CEO of Kick It Out, Roisin Wood said: “We’re seeing a lot of reports of ‘go back to where you came from’ which we haven’t seen for a while which seems to be on the back of Brexit.” Economic consequences aside, Brexit has intensified racism in the UK, with 71% of people from ethnic minorities reporting they’ve faced racial discrimination – an increase from 58% in pre-Brexit Britain.

The point is that politicians, while seeking to solve the problem, exacerbate it through their language and legislation. We can’t expect to extinguish the fire when the politicians in charge add fuel to the inferno.

So, perhaps looking to politicians for the solution isn’t the optimal strategy – who would’ve thought?

But what of those who can make a difference? What about the social media companies whose platforms provide the necessary environment for hate to be propagated? If racism is an attitude that won’t ever go away, could we not at least punish those who decide to spew their racist musings all over social media?

This question has been asked time and time again, and the government has routinely turned to legislation as their rebuttal: a response proven to be ineffective.

It seems so simple: when people create an account, make them upload some form of identification, so that if they decide to racially abuse someone online, they can be tracked down and punished. If it’s so simple, why haven’t they enacted it?

These days, people don’t want to give out their personal data; scandals like Cambridge Analytica perhaps justify that tendency. But there must be some way for these companies to track down these individuals. A way that could protect anonymity online but punish those who abuse it.

It’s a shame that we’re now at a point where this seems like a last resort. But it’s time to hold these companies to account, and explore the ways through which we can rid the game – and wider society – of this poison.