Capoeira Football: Afro-Brazilians in the Making of Jogo Bonito

Words can feel inadequate when trying to capture the particular elegance and exuberance of the great Brazilian footballers.

The metaphor of dance has eased the writer’s plight, evoking this rare fusion of flair and frivolity. The link between dance and football also plays out in a literal sense.

Raphinha, Vinicius Jr, Lucas Paquetá, and Neymar Jr dance at the 2022 World Cup

This connection was not forged in the mind of the despairing writer.

The entanglement of o jogo bonito and dance stretches back to the 1930s, a decade in which a new national identity, or Brasilidade, was projected by the populist regime of Getúlio Vargas.

Afro-Brazilians, previously marginalised in soccer and society, were recruited to define a new Brazilian game for this new Brasilidade.

Under their influence, jogo bonito would draw from the ancient sport of Capoeira.

Today, Capoeira is practised in 152 different countries

Brought to Brazilian shores by enslaved Angolans, Capoeira was dance, martial art, and philosophy rolled into one. It resonated with the impoverished black Brazilian, prizing an ingenuity also needed in everyday life. Current practitioner Mestre Amunka captures its wider symbolism in his poem ‘A Good Capoeira.’

“Like life always changing / always adapting, always shifting / Life is movement / Capoeira never stops.”

This spirit would infuse jogo bonito. Just as they jinked around jeopardy in life and Capoeira, Afro-Brazilians would dodge and deceive defenders.

Before Jogo Bonito: Racism and Rice Powder

Far from its headline act, the Afro-Brazilian resided in the margins of national football before 1930.

Racial hierarchy in society was mirrored in football: black Brazilians were actively excluded from Rio and São Paulo’s top leagues.

Francisco Carregal became the first black Brazilian to play in national competitions when he featured for Bangu Athletic Club in 1904. In response, the Liga Metropolitana de Sports Athléticos moved to exclude black players. In 1907, it was announced that “the directorship of the league… resolved by unanimous vote that persons of color will not be registered as amateurs in this league.”

The malaise is reflected in the career of Arthur Friedenreich. Born in São Paulo to a white German father and a black Brazilian mother, ‘Fried’ grew into a talented footballer renowned for his electric dribbling.

He played a starring role as Brazil won their first Copa America in 1919: “the most perfect centre forward of the South American championship” according to the Uruguayan captain.

Though Fried could exist within Brazilian football as a mixed-race man, it was only as one who distanced himself from blackness. For the Brazilian journalist Mário Filho, reflecting in 1947, Fried was the “mulatto who wanted to pass for white.”

Other mixed-race players retreated from blackness in a more literal sense, reflecting the contingency of their place in Brazilian football. Ahead of an appearance for Fluminense in 1914, Carlos Alberto applied rice powder to his face in a bid to appear white.

Fluminense fans now throw rice powder in honour of Carlos Alberto

Fried’s stardom, then, does little to alter the picture of a football clouded by racial hatred.

Making Jogo Bonito: Populism, Nationalism, and the Black Diamond

By 1938, Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre could point to characteristics of a distinctly Brazilian football, one shaped by the Afro-Brazilian.

“The qualities of surprise, malice, astuteness, and agility, and at the same time brilliance and individual spontaneity… the roguery and flamboyance of the mulatto that today is every true affirmation of what is Brazilian.”

Once hidden beneath rice powder, Afro-Brazilians were now the faces of Brazilian football.

Getúlio Vargas, who led a provisional government from 1930 until 1934, ruled as elected president until 1937, and then as dictator until 1945, was pivotal in the transformation of Brazilian nationalism and football.

Getúlio Vargas giving one of many speeches that characterised his populist style

Football was implicated in Vargas’ populist politics and his nation-building.

He staged rallies at football stadiums, pairing political announcements with exhibition matches. During the 1941 May Day celebrations at the Sāo Januário stadium in Rio, Zizinho was the headline talent in a friendly match marking the creation of the Labour Justice.

The new nationalism, at least theoretically, accepted Brazil’s racial diversity. For Gilberto Freyre, the country’s “racial democracy” made it a “tropical China:” a country approaching rapid economic development.

This new Brasilidade filtered into football. As the historian Maurício Drumond writes, “the formation of a new national identity was being forged, and football was being portrayed as a truthful representation of the alleged Brazilian unique racial mixture.”

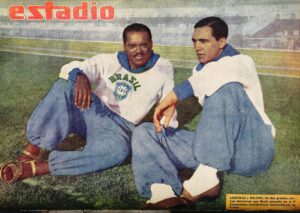

Domingos da Guia and Leônidas da Silva, two black Brazilians, defined national football during the 1930s.

Domingos, a defender, called his game “as Carioca as the best samba.” The evasion and invention he showed on the pitch was an extension of his lived experience as a black Brazilian.

“I often saw black players… get whacked on the pitch, just because they made a foul or sometimes for less than that… my elder brother used to tell me: the cat always falls on its feet. Aren’t you good at dancing? I was and this helped my football… that short dribble I invented imitating the miudinho, that type of samba.”

Meanwhile, Leônidas earned the nickname ‘Black Diamond’ through dazzling attacking play. He possessed the malícia (cunning) of the Capoeirista and the natural affinity with a football common to all Brazilian greats.

“The ball was one of my passions and the great ideal that inspired me was converting myself into a complete craque (star).”

Leônidas was the first Brazilian star who danced with the ball.

Tasked with reflecting on a decade of definition, Gilberto Freyre found adequate words for his 1938 article ‘Football Mulatto.’

“The Brazilian mulatto de-Europeanized soccer, giving it the curves… the grace of dance.”