Tris Dixon: Where Is Boxing’s Brain Trauma Outrage?

How does a sport that has been talking about ‘punch-drunk syndrome’ for almost a century still not take brain injury seriously? How does a sport which has seen its greatest champions publicly degenerate not educate its athletes about its effects? How can the story of brain injury in boxing still be said to be ‘untold’?

Tris Dixon does not claim to have the answers to these questions, but in his book Damage: The Untold Story of Brain Trauma in Boxing, he wants to challenge the sport to start asking them.

Dixon edited Boxing News for five years, has written books with Ricky Hatton and about Floyd Mayweather, and spent months on America’s Greyhound bus network tracking down fighters who fell from grace or never rose to it.

His credentials are impeccable, and it is his love of the sport that has led him to call on it to do better by its fighters: “When you talk about it to the old-timers, because they haven’t addressed it in the past, the reaction is often, ‘Ooh, [talking about brain trauma] is not good for the sport.’

“Well, what’s also not good for the sport is all these guys struggling in life after boxing, not knowing what’s happened to them and what damage they’ve taken on board.”

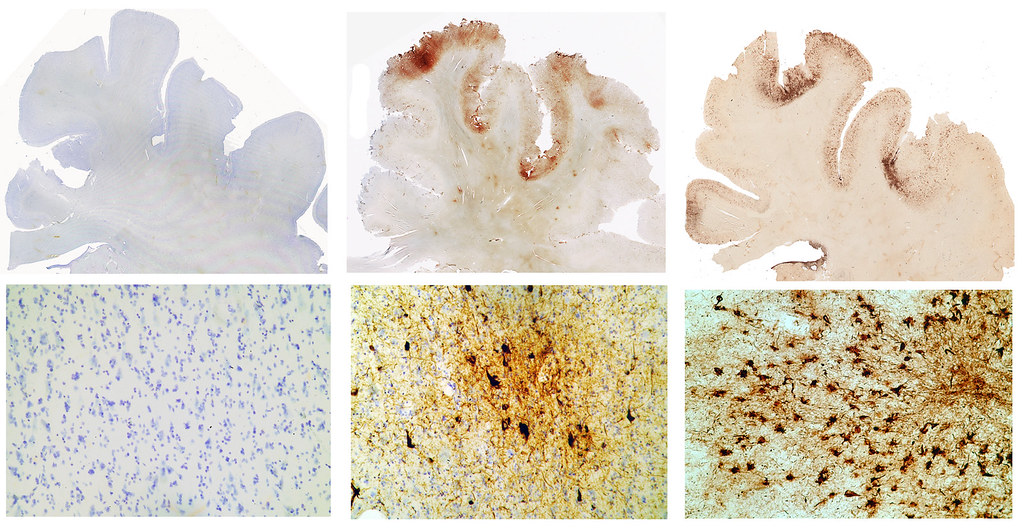

Brain trauma in boxing first emerges in the medical literature in 1928, under the flippant moniker ‘punch-drunk’ syndrome. The terminology has since shifted to dementia pugilistica, and now the more technical chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

But Dixon explains how the legacy of those early years persists even now: “When you look through the old neurological papers, it was said that [it] happened to sparring partners, to bad fighters, that you were pretty bad if you got it. It was thought that the more skilled fighters would never get it.

“It was a negative connotation of being ‘punchy’. I still see it now, people on social media talking about [fighters] being ‘punchy’ and ‘punch-drunk’ – it’s a really derogatory term in our sport.”

This association of brain trauma with being a bad fighter has been emphatically disproved, time and again. Dixon doesn’t have to think before reeling off a who’s who: “Five of the greats ever. Five people in anyone’s top 10: Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson, Henry Armstrong, and Willie Pep.

“All between them had Parkinson’s, dementia, or Alzheimer’s, or long term brain damage.”

Lest anyone think that these are problems of a bygone or less enlightened age, the passage of the decades has not led to significant athlete education or regulation to help modern fighters make free and informed choices.

Dixon points to one of the sport’s modern superstars: “When Anthony Joshua lost to Andy Ruiz, it later came out that his trainer Rob McCracken, who I’ve got a great deal of respect for, knew Joshua was concussed and he let him box on with a concussion.”

McCracken was heavily criticised by brain charity Headway, who accused McCracken of failing to protect Joshua from potentially fatal injury. And in his attempted clarification, McCracken inadvertently painted an even more troubling picture when he reminded us that boxing has no formal in-bout concussion assessment.

There are no doctors stepping into the ring to examine fighters, although in any case according to research groups like the Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF) an in-ring examination amid the lights and roaring crowds and adrenaline is at best useless and at worst actively dangerous. A proper assessment needs calm and quiet and time, all things that are in short supply when you step through the ropes.

And, as Dixon points out, fight night is only scratching the surface: “When I spoke to Chris Nowinsky [co-founder of the CLF, and former college American footballer and pro wrestler who wrote a game-changing book on brain trauma in gridiron that became an award-winning documentary], he said that he spoke to several fighters, and most of them said 90% of their damage is done in sparring.

“When fighters start as amateurs they should be made aware of it. Even though it might freak them out, they need to know. Some of them are even showing signs of damage after their amateur careers before they go into the pros. The trainer should be the first port of call, because they’re the ones who can monitor a fighter through that fighter’s career.”

Joshua himself revealed an alarming lack of understanding, and one that underlines the urgent need for books like Dixon’s: “Definitely they call it concussion…That’s what they call it. But I think concussion is a weak term. You’ve got to be stronger than it. You’ve got to fight through the concussion if you can.”

When one of boxing’s modern figureheads, an engaging and seemingly thoughtful intelligent person who has spoken openly about his issues with mental health, believes that brain trauma is something to be fought through, a weakness to be overcome, a cop-out, how much has the sport really changed since the inter-war days of ‘punch-drunk syndrome’?

Throughout our conversation, Dixon returns repeatedly to the failings and powerlessness of boxing’s governing bodies: “It doesn’t speak well of how [Joshua’s] been educated by the British Board of Boxing Control or Team GB or his amateur coaches if he’s got to where he’s got and he doesn’t understand what concussion is.”

Dixon argues persuasively that the proliferation of governing bodies makes consistent policy-making next to impossible even if the will were there to do so: “What boxing really needs is an umbrella organisation, even if it’s just a medical organisation, where brain scans can be uploaded and monitored and tracked. So if someone’s fighting in Germany, and they come over here to fight, we can follow their scans and their progress and their brain scans over time.

“Whereas at the moment, someone could fail a test in New York, and go get a license in California. And we’ve seen some examples where someone’s been suspended based on losing a fight by stoppage, so by a head injury, and they’ve gone and fought somewhere else, they’ve found a loophole, and been killed.”

There is an anger, borne of a protective love for the sport and its people, in Dixon’s analysis: “Frank Bruno’s been sectioned. Ricky Hatton’s struggled with depression and suicidal tendencies. Joe Calzaghe came off the rails as well. Tyson Fury, another one struggling with depression – depression is one of the big side effects of CTE. So it’s not weird. It’s happening to all these guys.”

We come back to the question of how the story of brain trauma in boxing can still be said to be untold, and even though Dixon knows why he still expressed amazement: “I’m still waiting for boxing to get this big surge that we’ve had through rugby league, through rugby union, through the NFL, and through soccer. Where’s the boxing outrage?

“No-one seems to be picking it up, none of the big sportswriters or media guys. Is it boxing? I don’t know. But have people looked into it? No, they haven’t.”

Dixon has looked into it. He has done so exhaustively. He has done so passionately. And it is up to the sport he so loves to start listening.